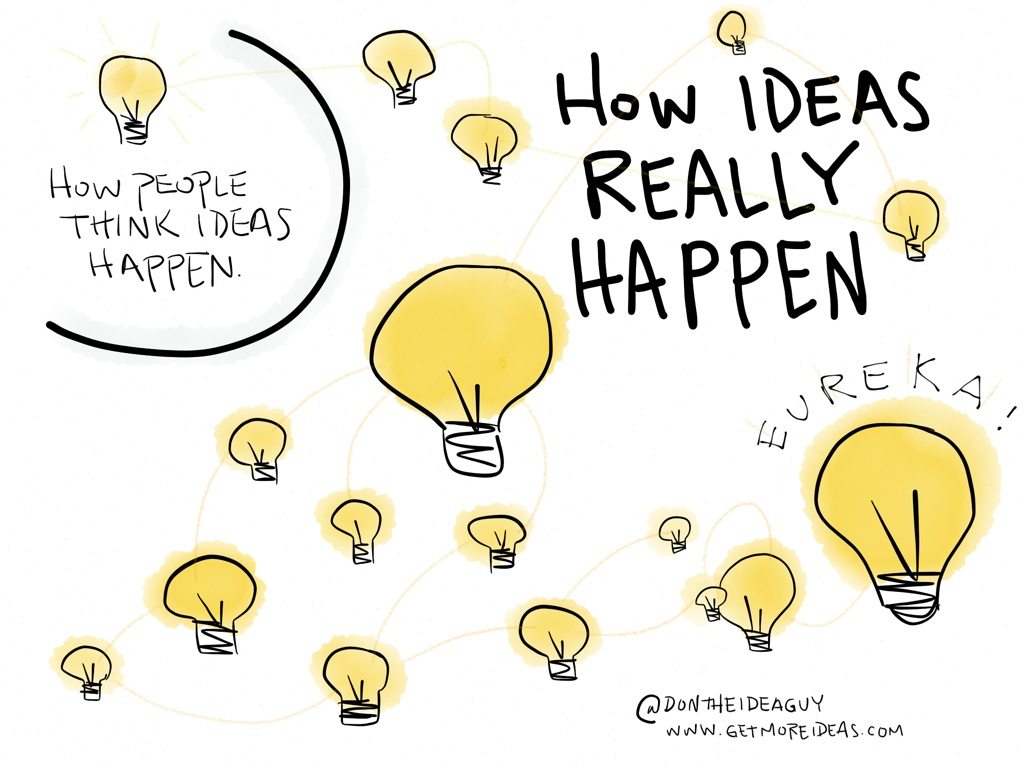

How Ideas Really Happen

I think the thing that frustrates most people about the process of coming up with ideas is that they believe in a singular moment of creative clarity. That there is an individual “A-HA!” moment where the perfect idea presents itself to the person who needs that exact idea at that exact moment.

The process is far more convoluted and rife with false starts, blind alleys, dead ends, return-to-start moments than anyone ever suspects.

The creative mindset includes the following characteristics:

- OPEN

Allowing yourself to simply be receptive to new ideas wherever and whenever they are want to present themselves. One needs to admit that ideas are all around, inspiration comes from everywhere, and you simply need to let yourself be open to possibilities. - ALERT

Once you’ve laid out the proverbial welcome mat for new ideas, you need to be aware enough to recognize a creative thought when it is happening. The ordinary person offhandedly ignores the early brain-tickling of an idea being born or fails to recognize the potential in a half-formed concept or image that pops into their head. - DISCIPLINE

Even if you are Open and Aware, it takes a personal force of will to actually document an idea when it manifests. Those that do recognize an idea frequently haven’t developed the habit of immediately capturing the concept. Statistically, the best ideas arrive at inconvenient times (while you’re half-awake in bed, or taking a shower, or out jogging, or during your morning commute). You tell yourself that you will recall the concept and write it down later (even though your inner voice is screaming at you about the last three ideas you lost because of this exact same delay.) - COGNITIVE

Probably most vital to the process is being able to find connective tissue between raw concepts and the ideas needed to solve the problem you are battling. It’s usually taking elements from several earlier ideas — some related to your current project and some that you’ve simply filed away from your own (or others’) past experiences — and combining them in a way that creates a sort of “Frankensteidea” whose whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

Adopting and developing these individual characteristics will make you far more likely to find that one great idea when you need it, but only because you were willing to sort through many more not-so-great ideas in preparation of a future “Eureka!” moment.

.